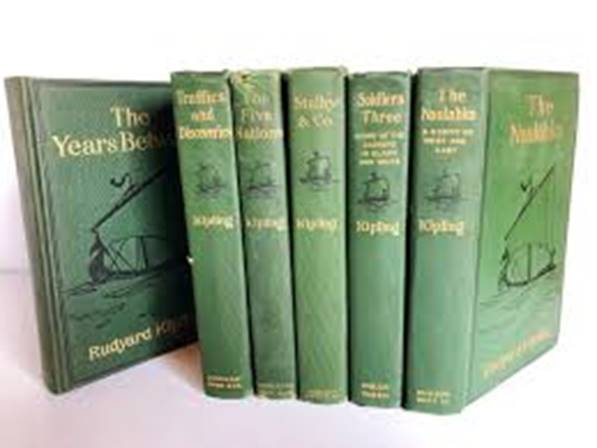

Besides fulfilling his journalistic commitments, he was able to compose some poetry on the side. In the six years he spent in Lahore, he published six volumes of short stories. The most famous, Plain Tales from the Hills, was based on his life experiences in India - Cowboy State Daily

Rudyard Kipling, the Imperialist Who Never Forgot India

By Dr Syed Amir

Bethesda, MD

It is often remarked that Rudyard Kipling loved India but hated Indians. Born in Bombay in 1865, when the British Empire was at its zenith, he was a prolific poet, an author, and the first Englishman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Kipling was long excoriated as a colonialist, but in recent years, his reputation has partially been rehabilitated. The realization has emerged that his literary work, set mostly in India, betrays his deep fondness for the country, representing the legacy of his early years spent growing up there. Nevertheless, at times, he felt rootless. In a comprehensive biography of Kipling, author Andrew Lycett quoted him saying, “England is the most wonderful foreign land I have ever lived in.”

Over the years, several books and research articles have critically analyzed the literature corpus he generated. An earlier biography, Rudyard Kipling, A Life, by Harry Ricketts, narrated his life story and brought much information about him to light. Two of his ballads, “East is East” and “The White Man’s Burden,” have become classics. The Jungle Book is considered among his most popular books.

Kipling had acquired a special sentimental bond with India, its culture, traditions, and values, from which he could never free himself. His father, an artist and craftsman, had settled in Bombay in 1865, employed by the School of Art and Industry. The opening of the Suez Canal greatly accelerated the city's evolution from a sleepy town to the Gateway of India. Kipling had a happy childhood, spoilt rotten by his Goanese Ayah, whom he never forgot. Later, he would fondly recall how her melodious songs lulled him to sleep. As a small child, he learned the local language and spoke to his parents in English, “haltingly translated out of the vernacular idioms that one thought and dreamed in,” he was to recall years later in his autobiography, Something of Myself, published posthumously.

The happy childhood was soon to come to an end. As was the custom among European residents of India at the time, his parents took him and his sister to live with a family of strangers in England. Kipling was under six years old, and his sister was even younger. Sea travel from India to England was long and arduous, and the children did not see their parents again for the next five years.

Kipling had a very miserable time during his stay with his foster family, unlike the loving household he left in Bombay. He later nicknamed the house in England as the “House of Desolation.” His foster mother, a strict Evangelical Christian, expected unreasonably good behavior and enforced rigid discipline, especially on him. The mental and physical abuses suffered at her hands left lasting scars on Kipling’s psyche.

He returned to India in 1882 and moved to Lahore, where his father was the city museum curator; he was less than 17 years old and had been out of the country for eleven long years. He was offered a job as a sub-editor with the Civil and Military Gazette, housed in two wooden sheds within the European quarters.

His parents occupied a large bungalow on the old Mozang Road. However, its surroundings were so bleak and barren that they reminded everyone of a desert; it was named Bikaner House to reflect its neighborhood. His father instinctively disliked trees; otherwise, Lahore had plenty of trees and greenery. Compared to his life in England, Kipling lived in luxury in a vast mansion with many servants. These comforts aside, he found life in Lahore lacking in recreational opportunities of the kind he sought. Much of the isolation was self-generated. Only about 70 European families were living in the city, and their contacts with the Indians were virtually nonexistent.

Kipling had a difficult relationship with his editor yet thrived at the daily paper. Besides fulfilling his journalistic commitments, he was able to compose some poetry on the side. In the six years he spent in Lahore, he published six volumes of short stories. The most famous, Plain Tales from the Hills, was based on his life experiences in India.

Although gaining fame and recognition, Kipling was progressively getting bored with life in Lahore and had taken to wandering late at night in quest of some distraction, visiting liquor shops, gambling casinos, and opium dens. His autobiography provides a fascinating account of this phase of his life.

Finally, he left Lahore to work with the Gazette’s sister publication, Pioneer, at Allahabad. In 1889, he left India for good, except for a brief visit in 1891 to his parents in Lahore and Ayah in Bombay. Kipling never returned to India. Even when the viceroy, Lord Hardinge, sent a special invitation to him to attend the Durbar to celebrate the coronation of King George V in Delhi in 1911, he declined, the only one to do so. The ten years he spent in Lahore and Allahabad led to the creation of five volumes of poetry, Departmental Ditties.

When he returned to England, Kipling had already become a famous and well-respected author and poet. His creative talents were still on the rise when he authored perhaps the most famous of his literary works: the children’s book Just So Stories and the spy novel Kim, set in India. In 2001, Kim was judged among the 100 best works of literature of the 20 th century. Kipling was offered a knighthood and the position of poet laureate, but he declined both honors.

While accolades were accumulating, tragedies were soon to intrude upon his life. First, his six-year-old daughter, Josephine, died while the family was on a brief visit to New York. Later, in 1915, he was devastated when his 18-year-old only son, John, was tragically killed on the Western Front in the First World War. During Kipling’s lifetime, neither his son’s body nor his grave was identified. After the loss of his son, he became morose and bitter. “His poem, My Boy Jack, is one of the most moving pieces of writing to come out of the war." In 1992, the Records Officer of the Commonwealth War Graves Commissions identified the grave of John Kipling at St Mary's Cemetery in Haines , France. By that time, Rudyard Kipling had been dead for many years.

In the twilight years of his life, Kipling continued to write and travel and also got involved in patriotic causes, raising money for the Boer War in South Africa and the First World War. He died in England in January 1936, coincidentally three days ahead of King George V, with whom he had developed a close personal friendship. In his obituary, the London Times Literary Supplement commented that “he was a national institution, but no longer a literary one.”

Over three-quarters of a century has elapsed since Rudyard Kipling's death. His literary legacy and actual place among the literary icons of the past century are subjects of debate. In his lifetime, he was considered an unabashed imperialist, believing in the moral mission of Western Christian nations to civilize the people of Asia and Africa. Today, he is mainly recognized as a superb children’s storyteller who viewed the world through the prism of his own period, much as most of his countrymen did. The final verdict on Kipling’s place as a writer and poet is yet to be rendered. Meanwhile, countless generations of children, unconcerned with shifting political mores, will continue to be enthralled by his Jungle Book and other short stories.

(Dr Syed Amir is a former Assistant Professor, Harvard Medical School, and a health science administrator, US National Institutes of Health)