Spotify

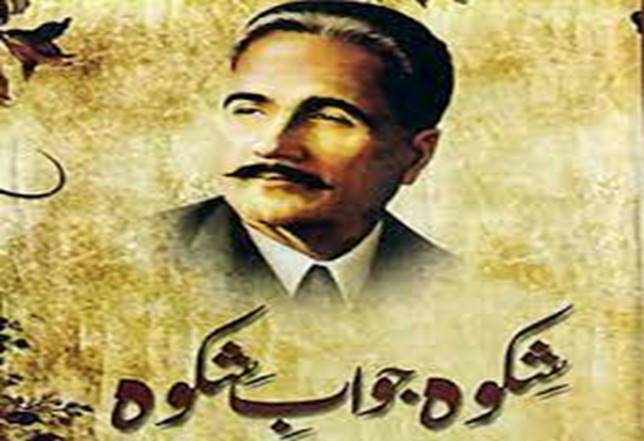

A Comment on Shikwa and Jawab e Shikwa of Allama Iqbal – Part 3 of 6

By Dr Nazeer Ahmed

Concord, CA

“Thay Tho Aaba Woh Tumhare He Magar Tum Kya Ho”

Your forefathers, indeed they were! But what are you? – Jawab e Shikwa

The Golden Age of Islamic science, spanning from the 8th to the 13th centuries, represents a remarkable era in human history where the Islamic world became the global center of knowledge, innovation, and scientific progress. During this period, Muslim scholars not only preserved ancient knowledge from Greek, Persian, Indian, and other civilizations but also expanded it, laying the groundwork for the fields of modern science and technology.

A key factor in the success of this era was the establishment of renowned centers of learning, with Baghdad's House of Wisdom (Bait al-Hikma) being the most notable. Founded during the Abbasid Caliphate under Caliph Harun al-Rashid and further developed by his son Al-Mamun, the House of Wisdom became a hub for the translation and study of scientific texts. Scholars from diverse backgrounds—Greek, Persian, Indian, and Chinese—converged in Baghdad to collaborate, debate, and innovate. The translation movement involved converting classical texts into Arabic, which made the works of Aristotle, Plato, Ptolemy, Hippocrates, Euclid and Aryabhatta accessible to the broader Islamic world.

Other significant centers of learning emerged across the Muslim world including Cordoba in Spain, Cairo in Egypt, and Samarkand and Bukhara in Central Asia. These centers housed extensive libraries such as the Library of Cordoba, which contained hundreds of thousands of manuscripts, exceeding by factors the collections in contemporary European libraries.

The translation movement was a defining feature of this era. It was not merely about preserving ancient knowledge but also about critically examining and building upon it. Muslim scholars approached Greek philosophy and science with both reverence and a spirit of inquiry, leading to advancements that far surpassed the original works. For example, while Greek mathematicians like Euclid laid the foundations of geometry, Muslim scholars like Al-Khwarizmi introduced algebra, transforming mathematics into a more sophisticated and practical discipline.

In mathematics, Al-Khwarizmi (780–850), often called the "father of algebra," wrote Kitab al-Mukhtasar fi Hisab al-Jabr wal-Muqabala (The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing), which systematically introduced algebraic methods. His work laid the foundations for solving linear and quadratic equations, and the term "algorithm" is derived from his name. Another mathematician, Omar Khayyam (1048–1131), developed methods for solving cubic equations and contributed to the development of a more accurate calendar.

Astronomy was another field where Muslim scholars made significant advancements. Al-Battani (850–929) refined Ptolemy’s measurements and calculated the solar year’s length more accurately. His astronomical tables influenced European astronomers like Copernicus. Similarly, the astronomer Ulugh Beg (1394–1449) built one of the largest observatories in Samarkand, where he compiled a star catalog that provided precise measurements of celestial bodies. His work was highly respected and remained the most accurate for centuries.

Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 965–1040), known as the "father of modern optics," made groundbreaking contributions to the study of light and vision. His Book of Optics corrected many of the misconceptions held by earlier Greek scholars and laid the foundation for modern physics. He was the first to correctly explain that vision occurs when light reflects off an object and enters the eye, contrary to the Greek theory that the eye emits light rays. Ibn al-Haytham’s work on the scientific method, emphasizing experimentation and empirical evidence, was ahead of its time and influenced later Western scientists like Roger Bacon and Johannes Kepler.

Medicine was another area where Islamic scholars excelled. Al-Razi (Rhazes, 854–925) and Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980–1037) were among the most celebrated physicians. Al-Razi wrote comprehensive texts on clinical medicine, including Kitab al-Hawi (The Comprehensive Book on Medicine), which was used as a medical reference in Europe for centuries. He was the first to differentiate between smallpox and measles and advocated for evidence-based medical practice. Ibn Sina's Canon of Medicine became the standard medical text in both the Islamic world and Europe until the 17th century. His work covered various topics, from anatomy and pharmacology to psychology, and emphasized the importance of hygiene and diet in disease prevention.

In the field of chemistry, Jabir Ibn Hayyan (Geber, 721–815) is often hailed as the "father of chemistry." He introduced methods of experimentation, crystallization, distillation, and evaporation, which laid the groundwork for modern chemistry. Jabir’s classification of substances and his emphasis on laboratory practices were revolutionary for his time.

Significant, indeed revolutionary strides were made by Muslim engineers and inventors. Al-Jazari (1136–1206), a polymath and mechanical engineer, wrote The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, which described over a hundred mechanical inventions, including water clocks, automated machines, and even a rudimentary robot. His work laid the foundation for modern engineering and robotics. He was the inventor of the cam shaft which made possible the conversion of linear motion into rotary motion. Without this invention, we would have no automobiles or trains.

The field of civil engineering saw innovations like the construction of water wheels, dams, and irrigation systems. Master architects like Sinan in the Ottoman Empire designed magnificent structures that blended aesthetics with functionality, influencing architectural styles worldwide.

The introduction of paper, a technology borrowed from the Chinese, played a crucial role in the dissemination of knowledge. Paper mills were established across the Islamic world, making books more accessible and facilitating the spread of scientific ideas. This development allowed scholars to share their findings widely, contributing to a vibrant culture of learning and scholarly exchange.

Islamic philosophy during the Golden Age was characterized by attempts to reconcile reason and faith. Philosophers like Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, and Ibn Rushd explored the relationship between science, metaphysics, and religion. Al-Farabi (872–950) developed a classification of knowledge and sought to harmonize the teachings of Plato and Aristotle with Islamic theology. Ibn Sina's Metaphysics influenced not only Islamic but also Western Christian thought, while Ibn Rushd’s commentaries on Aristotle laid the groundwork for the European Renaissance.

These philosophers believed that the study of nature was a way to understand God’s creation, an idea that was supported by Qur'anic teachings encouraging the exploration of the natural world.

In summary, the Golden Age of Islamic Science was a period marked by extraordinary contributions across multiple disciplines. The era's scholars laid the groundwork for many fields that would later flourish in Europe, highlighting the Islamic world’s critical role in the history of science and human progress. However, the decline that followed was shaped by a complex interplay of external invasions, internal strife, and philosophical shifts, setting the stage for a scientific stagnation that persists even to this day. (Continued next week)

( The author is Director, World Organization for Resource Development and Education, Washington, DC; Director, American Institute of Islamic History and Culture, CA; Member, State Knowledge Commission, Bangalore; and Chairman, Delixus Group)