The film Jinnah (1998) was conceived by two Pakistani expats - Akbar S. Ahmed and Jamil Dehlavi. The actor chosen to play Jinnah - Christopher Lee – had made his name in horror films. Nevertheless, Lee relished the role, describing it as ‘the most important’ he had ever played

Reimaged Idols

By F. S. Aijazuddin

Until the 1960s, no member of the British Royal Family could be portrayed on the stage or on screen. The character had to have been dead for at least fifty years.

Queen Victoria became fair game after 1951 (the fiftieth anniversary of her death). Even as late as 1957, when The Prince and the Showgirl was made, Marilyn Monroe could be shown shaking only the gloved hand of Queen Mary.

The television series The Crown has put paid to all that. It is the saga of a parallel royalty. The last episode brings the story up to the death of Queen Elizabeth II in September 2022 - history in real time.

The screen reimaging of our sub-continental idols has been cautious. Hollywood began with films like Nine Hours to Rama (1963) about Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination and then David Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982), which narrated his fuller life. The latter film won 8 Oscar awards, including one for Best Costume Design. (How does one design a homespun loincloth?)

Bollywood was slower off the mark. Some like Gulzar’s Aandhi (1975) and Amrit Nahata’s Kissa Kursi Ka (1975) were released during Mrs Gandhi’s prime ministership. Too close to the knuckle, they ran foul of the censors.

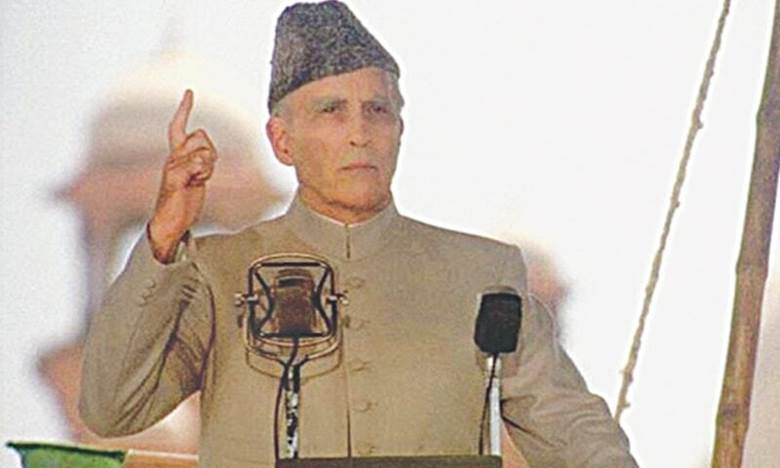

Inevitably, someone felt Quaid i Azam M.A. Jinnah deserved also to be elevated to the screen. The film Jinnah (1998) was conceived by two Pakistani expats - Akbar S. Ahmed and Jamil Dehlavi. The actor chosen to play Jinnah - Christopher Lee – had made his name in horror films. Nevertheless, Lee relished the role, describing it as ‘the most important’ he had ever played.

He gave a surprisingly credible performance of the man whose life and achievements the biographer Stanley Wolpert summarized in this pithy paragraph: ‘Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state. Muhammad Ali Jinnah did all three’.

Every new nation attributes its existence to one person, a Father of the Nation, responsible for its paternity. Prominent amongst them, for example, were Soekarno in Indonesia, Kenyatta in Kenya, Ben Bella in Algeria, and Nkrumah in Ghana. To Bangladeshis, it is Banglabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Sheikh Mujib’s life can be split into two halves – from his birth in 1920 to Pakistan’s independence in 1947, and the second from 1947 until his assassination in 1975. Shyam Benegal’s recently released biopic Mujib: The Making of a Nation (2023) covers both, with commendable sensitivity.

Such a film, sponsored by the Bangladesh government of PM Hasina Javed (Mujib’s eldest surviving child) and the Indian government could have been clouded by bias. (Attenborough’s Gandhi reeked of Mrs Indira Gandhi’s benediction). In fact, Shyam’s film is free of sponsored prejudice.

The film is playing to packed houses in Bangladesh. It could be shown safely in Pakistan, without risking a riot.

The film opens with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s return to Dhaka on 10 January 1972, after President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto ordered his release from jail in West Pakistan. The story then reverts to his early years, his tutelage under the Bengali leader Hossain Shaheed Suhrawardy (PM briefly from September 1957 to October 1958 of a united Pakistan), and his demands for equitable treatment for a neglected East Pakistan.

Confrontation with General Ayub Khan’s military government led to stints in jail. In 1966, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman announced his neo-secessionist six-point plan.

The general election held in 1970 gave Mujib’s Awami League a majority in the National Assembly. That proved indigestible to President Yahya Khan and to Mr Bhutto, who preferred to reign in a divided hell than to serve in a united heaven.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, exasperated by the unconscionable delay in the transfer of power to his party, gave an inflammatory speech at Dhaka’s Race Course maidan on March 7, 1971. He was rearrested and taken to West Pakistan, where he remained incarcerated until his repatriation in January 1972.

There are fleeting appearances in the film by Yahya and Bhutto, unavoidable images of the 1971 war, and a frank admission of Indira Gandhi’s midwifery. However, there is no reference to Mujib’s dramatic appearance (at Bhutto’s conciliatory invitation) at the 1974 Islamic Summit in Lahore.

On 15 August 1975, some Bangladeshi military officers did what their West Pakistani counterparts had threatened to do for years: they killed Mujibur Rahman. Benegal’s film ends with images of the blood soaked, contorted bodies of Mujib and his family, all except his daughter Hasina Wajed who happened to be abroad.

Benegal’s film on Mujib is less about Mujib’s political persona than about him as a demonstrative husband and a caring father. It is a tribute by Hasina to the father she shares with their nation. Dawn