The Flower Show in Washington

By Dr Syed Amir

Bethesda, MD

Every spring, America’s capital, Washington DC, comes alive with a spectacular show when thousands of cherry trees lining the tidal basin by the edge of the Potomac River start to bloom. The sparkling pinkish-white flowers covering the trees and carpeting the pavements give the fleeting illusion of a mid-winter snowfall. The cherry blossom festival this year is scheduled from March 20 to April 14, 2024. The Park Service estimates that the blossoms will reach their peak between March 23-26, consistent with a trend noted for the past several years that the peak moves sooner by a few days each year because of warm winters.

The festival, over decades, has evolved into a major tourist attraction and almost a million curious sightseers descend on the capital city every year. They come to enjoy the spectacular flower show, unique in America, and savor the view of some historic monuments within easy walking distance. The event is also a major source of income for the Washington area businesses as the tourists spend large sums of money, staying in hotels and dining at expensive restaurants.

The dazzling flower show is not the only attraction at the annual festival. During this time, the city showcases an array of colorful parades and floats, music shows, marching bands, art exhibitions, and a galaxy of cultural and sports events filling every day for two weeks. While most of the festival is open with free admission, there is a charge for reserved seats in special enclosures that offer superior views.

The visitors are entertained by nationally recognized and talented dancers and musicians who perform during the day-long events, while famous television artists lead the grand festival parades. According to official literature, “some 100 performances are expected on the stage this year, and a diverse array of dance styles, including Japanese, Eastern European, Indian, and Flamenco will show their talents. Ac claimed New York-based composer and instrumentalist Kaoru Watanabe will bring his signature skill by infusing Japanese culture with disparate styles to create an engrossing performance of music that is melodic, authentic, and engaging.”

The festival is not designed merely to amuse and entertain. One of its aims is to foster a spirit of goodwill and friendship among nations, especially between the United States and Japan. Goodwill ambassadors are chosen by the festival committee from among young people who are interested in studying the Japanese language and culture. In addition to promoting international friendship and harmony, the festival serves another very important function: it raises funds for various charities. The Festival Committee awards scholarships to talented high school students who need financial assistance to pursue college-level education. The charity funds also support some sports clubs for boys and girls in the poorer areas.

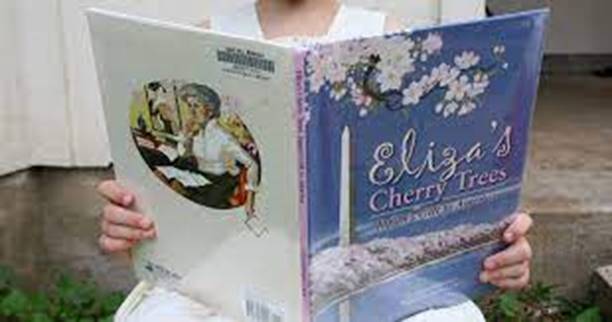

Washington's original cherry trees were brought here from Japan more than a century ago. The Festival’s Opening Ceremony is an artistic commemoration of the historic gift of flowers that were brought from Tokyo to Washington. The story of how they got here is both captivating and of historical interest. Their existence today owes much to the tenacity and perseverance of one woman, a gifted travel writer and photographer, Eliza Scidmore, whose name would not be recognized by most Washingtonians today.

Scidmore took a voyage to Japan in the latter part of the nineteenth century  something very unusual for women in those days — and fell in love with the blossoming cherry trees that she saw in abundance in the Tokyo parks. She is reported to have commented later in her book 'Except Mount Fujiyama and the moon, no other object has provided the theme and inspiration for so many Japanese poems as the cherry tree'

something very unusual for women in those days — and fell in love with the blossoming cherry trees that she saw in abundance in the Tokyo parks. She is reported to have commented later in her book 'Except Mount Fujiyama and the moon, no other object has provided the theme and inspiration for so many Japanese poems as the cherry tree'  .

.

Scidmore was determined to introduce cherry trees to her hometown, Washington. Alas, it did not prove to be an easy venture. The US capital in those days was a vile, deathly swamp where dreaded malaises such as malaria and yellow fever were rampant. Believing that the Potomac River might be the breeding ground for these diseases, army engineers decided to dry out the swamps. In the process, they reclaimed a piece of dry land which today is known as Potomac Park. Scidmore proposed that the Japanese cherry trees be planted on the recovered land to overcome foul-smelling dumps that infested the new grounds. Her pleas were politely heard but rejected by the government officials who, nevertheless, admired the pictures of the trees she had brought back from Japan.

Scidmore was not ready to give up. The inauguration of William Taft in 1909 as the 27th president of the US opened some new possibilities for Scidmore to pursue her favorite project. The First Lady, Helen Taft, had a strong personality and progressive views and admired the elegance of the cherry trees — having lived for some time in the Philippines and the Far East. When approached, Helen Taft readily agreed to sponsor the cherry tree project, as she thought that it would help beautify Washington, a city she considered a den of criminals and rendezvous of tramps.'

Soon, one thousand cherry trees, a gift from the Mayor of Tokyo, arrived, on March 27, 1912. Helen Taft and the wife of the Japanese ambassador, Viscountess Chinda, planted the first cherry tree in Washington. Today, more than 4,000 can be counted around the tidal basin alone, however, only about 150 of the original trees brought from Japan have survived after a century  The trees can also be seen in and around the Greater Washington area.

The trees can also be seen in and around the Greater Washington area.

The horticultural relationship with Japan has been mutually beneficial. In 1981, there was a reversal of roles, the Japanese gardeners came to Washington to obtain some cherry cuttings to take back, as one variety of their stock had been decimated by flood.

Eliza Scidmore lived long enough to see her project take full shape and her beloved cherry trees blossoming by the riverbank, providing much joy to the residents and visitors of the city. When she died in 1928, the Japanese government made a special request that her ashes be sent there to be interned with honor. It is ironic that while a plaque bearing the names of Helen Taft and the wife of the Japanese ambassador is in place at the spot where the first cherry tree was planted, the name of Eliza Scidmore is all but forgotten.

(Dr Syed Amir is a former Assistant Professor, Harvard Medical School, and a health science administrator, US National Institutes of Health)