Presented as an intellectual biography, in the book Irwin questions the judgment of some stalwart anthropologists, including Toynbee, who have reviewed it. He argues that a number of Ibn Khaldun’s statements in the Muqaddima are not compatible with what we know in the 21st century. He cites his observation that the Black Death was caused by “too much civilization and density of population that caused corruption of the air,” which in retrospect seems a little naïve - ImageNational Review

Allama Ibn Khaldun in the 21st Century

By Dr Syed Amir

Bethesda, MD

On May 19, 2006, Queen Sofia and King Juan Carlos of Spain opened an exhibition in Seville’s Alcazar, showcasing the work of Ibn Khaldun on his 600th death anniversary. (King Carlos retired in 2014 in favor of his son, King Felipe VI). Many dignitaries, including kings and prime ministers, attended the celebration held in the royal palace. The exhibition had on display some precious hand-written scholarly manuscripts and objects loaned from countries in North Africa, dating back to the period when Ibn Khaldun lived there.

The majestic Alcazar, one of the most beautiful monuments in the world, served as the official residence of Castilian kings for centuries after Sultan Muhammad al-Mu'tamid (1069–1091) was forced out of his kingdom. Interestingly, its stately corridors and magnificent audience chambers would be entirely familiar to Ibn Khaldun since, in 1364, he visited this palace on a diplomatic mission from Sultan Muhammed V of Granada to King Pedro at Seville.

Lauded as the greatest scholar, philosopher, historian, and social scientist who ever lived, Abd ar-Raḥmān ibn Muḥammad ibn Khaldūn al-Ḥaḍramī, popularly known as Ibn Khaldun, was born in 1332 in Tunis and traced his ancestry to South Yemen. He descended from a string of scholars and his father was a jurist of Maliki Fiqh. His family members originally arrived in Spain with the conquering Muslim armies and settled in Ishbilia (Seville). They served in high offices but, as Muslim power waned in Spain, were forced in 1248 to emigrate to North Africa, one of many Andalusian emigres. Ibn Khaldun died in 1406 in Cairo and is buried there.

The political situation in North Africa in the 14th century was particularly turbulent. After ravaging Europe and the Middle East, the plague, often referred to as the Black Death, had reached there. A demographic catastrophe, it wiped out almost one-third of the population, including Ibn Khaldun’s parents when he was sixteen years old.

Some other events unfolding at the time were also unsettling. The last Muslim enclave of Granada in Spain was in its twilight period and the various rulers of North African states were changing with unusual frequency, resulting from tribal wars and dynastic realignments. Consequently, Ibn Khaldun had to lead a peripatetic existence, always searching for stability in his life. These upheavals in and around him greatly influenced his thinking and informed his ideas about the genesis of historic changes that influenced much of his subsequent writings.

Ibn Khaldun was probably much relieved when in 1363 he was invited by Sultan Muhammed V of Granada to serve in his court where another scholar of great standing, his friend Ibn al-Khatib, a polymath, poet, and historian served as the vizier. The new position promised stability. A year later, Ibn Khaldun was sent by the Sultan on a diplomatic mission to the court of King Pedro of Castile. It is reported that the King was so impressed with the visiting scholar that he offered him a high position and promised to return all his ancestral lands that had been confiscated earlier, only if he would convert to Christianity. He declined. However, forced by palace intrigues, he left Granada and returned to North Africa after just two years.

The next phase represented the most productive phase of his life. In 1377, when he was 47 years old, he secluded himself in the castle of Ibn Salamah in eastern Algeria to concentrate on writing and consolidate his thoughts, drawn from long and wide-ranging experiences of life. He deliberated for four years and produced his revolutionary and landmark creation, the Muqaddima, (prolegomenon) or introduction to his more detailed work on the history of North Africa, named Kitab al-Ibar (book of lessons). The Muqaddima, however, is considered his opus magnus in which he developed his brilliant and original theory to explain the rise and fall of human civilizations. Ibn Khaldun singularly placed his trust in his own observations, ignoring anecdotal material which he claimed earlier historians had failed to do.

He argued that history was not just a compendium of events that happened haphazardly over time. There was a natural logic to how dynasties and kingdoms came into being, decayed, and disappeared. He introduced the term, asabiyah, (group solidarity) to emphasize the crucial role of loyalty among members of clans or tribes in achieving accomplishments. These characters were especially strong among raw desert nomads, untainted by indulgences of the urban life. Thus, nomads were able to overwhelm established empires, weakened by the soft and comfortable life. The new victors founded a new dynasty; the nomads in time having adapted to the comforts of urban life, lost their asabiyah, and then in turn were overtaken by another group of rugged tribesmen. Ibn Khaldun theorized that the cycle was completed in about four generations.

Until early 19th century, Ibn Khaldun’s remarkable contributions remained largely unrecognized by Western scholars. The renowned British historian, Arnold Toynbee (1889-1975) is credited with publicizing them, and extolling the Muqaddima “as undoubtedly the greatest work of its kind that has ever been created.” Since then, many scholarly books have been published on his work, mostly crediting him with the creation of the modern disciplines of sociology, historiography and anthropology.

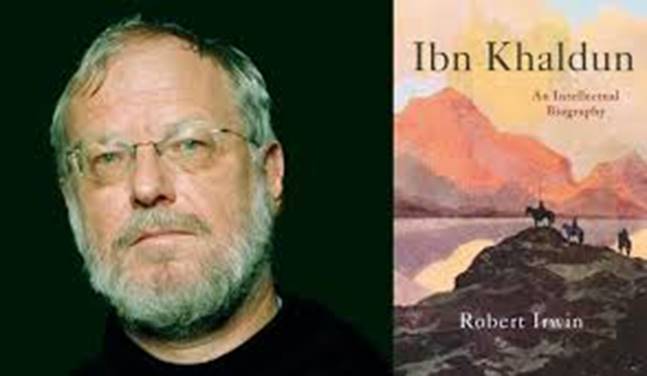

In a recent noteworthy book, Ibn Khaldun, Robert Irwin, a senior associate at the London School of Oriental and African Studies, has taken an unconventional approach. He questions some of the conclusions presented in the Muqaddima and their relevance in modern times. Asserting that Ibn Khaldun and his thinking was greatly shaped by his Islamic faith and immediate environment, Irwin contests claims that his theories remain valid in modern times. Irwin believes that many previous Western scholars read the Muqaddima with “their eyes glazed over.” Since “the book is so long, it has been selectively sampled and abridged. Its message has been modernized and rationalized” by the translators to comport with 21st century ideas.

Presented as an intellectual biography, in the book Irwin questions the judgment of some stalwart anthropologists, including Toynbee, who have reviewed it. He argues that a number of Ibn Khaldun’s statements in the Muqaddima are not compatible with what we know in the 21st century. He cites his observation that the Black Death was caused by “too much civilization and density of population that caused corruption of the air,” which in retrospect seems a little naïve.

Irwin does not question the value of the seminal contributions made by Ibn Khaldun. His polemics and his criticism of some aspects of the Muqaddima notwithstanding, they are unlikely to unseat the medieval savant from the lofty position he occupies in the pantheon of the world’s great scholars and thinkers.

(The writer is a former assistant professor, Harvard Medical School and a health scientist administrator, US National Institutes of Health)