At least in the world of literature, not only did the West and East ‘meet’ but one side also managed to somehow seep into the other, time and again - Photo The Villager

Eastern Influence on Western Literature

By Dr Zafar M. Iqbal

Chicago, IL

About the proverbial ‘East’ and ‘West’, when Kipling declared that “never the twain shall meet,” he had also acknowledged that “there is neither East nor West….” (line 3 from the same ‘The Ballad of East and West’).

At least in the world of literature, not only did the West and East ‘meet’ but one side also managed to somehow seep into the other, time and again. Literary traffic from the West to the East has been relatively heavy, and, for long. It wasn’t just Edward Fitzgerald introducing the English readership to Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyats in Persian and their exotic hedonist ambiance.

The Oxford Book of Quotations (1953 edition) lists over 180 phrases and lines from Fitzgerald’s translation of Khayyam, far exceeding those from Shakespeare. For instance, these have been pervasive enough to have now been absorbed into the English language:

'A jug of Wine, a loaf of Bread - and Thou beside singing in the wilderness'; 'Like Snow upon the Desert's dusty face’; 'The courts where Jamshid gloried and drank deep’; 'I came like Water, and like Wind I go'; ‘The Flower that once has blown forever dies'; 'And that inverted Bowl we call The Sky’; 'The moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on...’

Although the Persian purists identified problems of translation, etc., in Fitzgerald’s five editions (1859-1889),

as pointed out by Riz Rahim in her book, “In English, Faiz Ahmed Faiz” (2008), interest in Eastern poetry never diminished, and seems to have started even earlier.

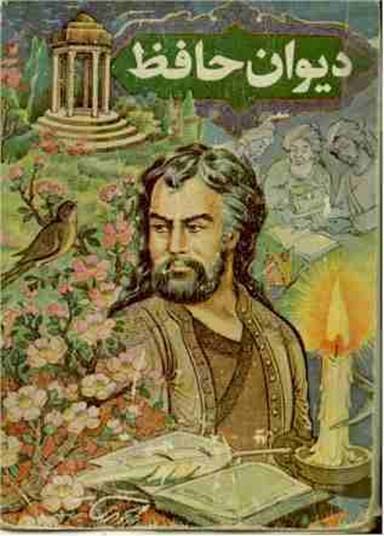

The best documented early figure seems to be Sir William Jones, an Anglo-Welsh polyglot, who in 1771, translated the first ghazal of the ‘Diwan-e-Hafiz’ as “A Persian Song of Hafiz, (a 14th-century Persian poet), that began with these lines so evocative of Eastern romanticism:

“Sweet maid, if thou would'st charm my sight,

And bid these arms thy neck infold;

That rosy cheek, that lily hand,

Would give thy poet more delight

Than all Bocara's note I vaunted gold,

Than all the gems of Samarcand…”

Jones had also written in Persian under the pen-name ‘YounisUksfardi’ (the first name, for Jones, last name, “from Oxford,” his affiliation). He became so interested in the Subcontinent culture that in 1784 he established the Asiatic Society in Calcutta and translated important Indian literary works. He spent his last years in India and is buried in a Calcutta cemetery.

Early in the 19th century, interest in Eastern poetry and philosophy began to spread to other European languages, when the Austrian orientalist Baron von Hammer-Purgstall translated the entire Divan of Hafiz (1812-13) into German, not in poetry but in meticulous prose (nearly 600 Ghazals, half a dozen Mathnavis, a couple of Qasidas, nearly four dozen fragments and six dozen quatrains). This inspired not just the German orientalists like Goethe (1749 – 1832) and Friedrich Ruckert (1788 –1866), who, with Edmund Alfred Bayer, translated ‘Aus Saadis Diwan’ of the12th century poet, Sa’adi. According to a well-respected orientalist, Annemarie Schimmel, Ruckert still has a strong influence on German pursuits in oriental studies.

Goethe wrote (1815-1819) West-Ostlicher Divan in German, or West-Eastern Divan, as a tribute to the famous 14th century Persian poet, Hafiz (about 1310–1325). It was not a translation of the poetry of Hafiz, but Goethe’s own attempt to use the themes and mood Hafiz conveyed. Even the titles of 12 books in Goethe’s Divan have a Persian flavor, such as Moghani-Nameh or Book of the Singer, Hafiz-Nameh or Book of Hafiz, Ishq-Nameh or Book of Lover, Tafakkur-Nameh or Book of Reflection, Hikmat-Nameh or Book of Maxims, Zuleika-Nameh or Book of Zuleika, Saki--Nameh or Book of the Cupbearer, Parsi Nameh or Book of the Parsees and Khuld-Nameh or Book of Paradise.

In Hafiz, Goethe found a kindred spirit, an idol, and addressed him as “Saint Hafiz” and “Celestial friend.” In Goethe’s “Divan,” his reverence for Hafiz and his philosophy is clear from these lines from different poems, for instance:

“HAFIS, straight to equal thee,

One would strive in vain; ….”

and,

“May the whole world fade away,

Hafiz, with you, with you alone

I want to compete! Let us share

Pleasure and pain like twins

To love like you, to drink like you,

This shall be my pride, my life.”

This bug of Eastern Dionysian philosophy also bit another generation of German thinkers, notably Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), who grew up on translations of Goethe and Hammer-Purgstall. After studying Hafiz and Goethe, Nietzsche declared them as the “subtlest and brightest” poets, with Hafiz being “an ideal poet” and “an oriental free-spirit” as he finds in “ Die fröhliche Wissenschaft ” (1882), which was translated in the first edition (‘The Joyful Wisdom’) and later with a new title and re-translated (“The Gay Science”), as “mocking blissfully” at the trials and tribulations, joys and sorrows, we all go through. Nietzsche refers to Hafiz nearly a dozen times in his writing, in addition to a poem entitled ‘An Hafis: Frage eines Wassertrinkers’ (To Hafiz: Questions of a Water Drinker). In this poem, Nietzsche admires the Dionysian approach of Hafz, “a water drinker,” to the world in these memorable words:

“… you are everyone and no one, you are the tavern and the wine

you are the phoenix, the mountain and the mouse

you keep pouring in yourself

and you keep filling with yourself

the deepest valley you are

the brightest light you are

the intoxication of all intoxication you are

what need do you have to ask for wine?”

Hafiz finally reached the US in 1838 when Ralph Waldo Emerson, an essayist-poet who led the Transcendentalist movement in the mid-19 th century America, read Goethe’s Divan and later Hammer-Purgstall’s German rendition of Hafiz. After that, Emerson called Hafiz a “poet for poets,” who found pleasure in the simplest things in life, and said, “He [Hafiz] fears nothing. He sees too far; he sees throughout; such is the only man I [Emerson] wish to see and be.” Emerson also added, “Hafiz defies you to show him or put him in a condition inopportune or ignoble. Take all you will, and leave him but a corner of Nature, a lane, a den, a cowshed ... he promises to win to that scorned spot the light of the moon and stars, the love of man, the smile of beauty, and the homage of art.”

Emerson took great interest in the poems of Hafiz and Persian literature and was equally impressed by the optimism of another sufi poet, Sa’adi. Through Emerson and Hafiz, one of my favorite American poets, Emily Dickinson, also reflected some Hafizian spirit in her poetry, particularly #214, in which she describes her “soul awareness,” spiritual intoxication -- a mystical state:

“I taste a liquor never brewed -

From Tankards scooped in Pearl -

Not all the Vats upon the Rhine

Yield such an Alcohol!....”

Coincidently, this sounds similar to Emerson’s metaphysical wine that ‘never grew in the belly of the grape’:

“ Bring me wine, but wine which never grew

In the belly of the grape, ….”

No discussion of English translations of Persian poetry and literature would be complete without acknowledging the impressive popularity of Coleman Barks’ translation of Rumi, the famous 13th-century Persian Sufi poet. Although Persian scholars and purists did not spare Barks, or for that matter Fitzgerald for Khayyam, English literature is richer nonetheless because of their contribution.

Literary traffic, as I mentioned before, has not just been from the West to the East. Iqbal has also been an active Eastern participant in what Goethe called “Weltliteratur,” or world literature, and thought "Poetry is cosmopolitan.” Iqbal’s “Payam-e-Mashriq” (1923), in Persian, was in response to Goethe’s “West-Osterlicht Divan” and contained many poems on Western themes and personalities (included in my forthcoming book on translation of Iqbal’s poetry). Even before he went to England or wrote ‘Payam’, Iqbal had written about a dozen poems in Urdu, based on or extracted from various English poets. Most of them are included in “Baang-e-Dara,” (in its 3rd section, from 1908). Here is my translation of Iqbal’s poem:

Shakespeare (Shakespeare)

For dawn, shimmering flow

of a river, its mirror;

for music at night,

tranquility, its mirror.

In leaves and flowers

lies Spring’s beauty;

for one who’s drinking,

future lies hidden in wine.

Beauty reflects truth and

heart, beauty;

for a human heart

your kind words, a mirror.

Your deep reflection,

a miracle of life.

Was it your clear-sightedness

that bared the secrets of life ?

When those who

wanted to learn such things sought you,

they found the sun

hiding in its own bright light.

You hid yourself from

the world’s eye, and

you saw the world

plain and clear.

Nature’s interest in

keeping its secrets safe is

such that

it won’t share them with others.