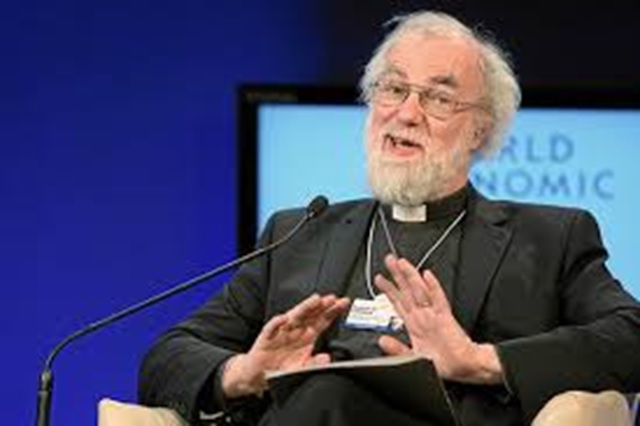

I have seen up close Williams’ commitment to interfaith dialogue and embracing non-Christians over the years in my meetings with him. Dr Amineh Hoti and I were invited to Lambeth Palace in 2012, for example, to attend one of Williams’ final public events as archbishop—which notably focused on interfaith engagement—and I was asked to deliver the keynote address in the afternoon session. At this event, the lectures of the archbishop to Muslim audiences in Egypt, Libya and Pakistan, which had been compiled into a volume and translated into Urdu and Bengali, were presented to the archbishop along with glowing speeches made by Muslims recording the contributions of the archbishop in promoting interfaith dialogue. After the official events he still found time to meet Amineh and myself separately with his usual courtesy and kindness – Dr Akbar Ahmed. Photo Theos Think Tank

Three Global Spiritual Leaders in a Time of War and Violence: Rowan Williams, the Compassionate Christian Scholar

By Akbar Ahmed*, Frankie Martin*, and Dr Amineh Hoti**

*American University, Washington DC

** University of Cambridge, UK

.

.

To reach the position of the Archbishop of Canterbury, head of the world’s Anglican faithful living in the historic Lambeth Palace, and then the Master of a Cambridge College, is about as high as you can ascend in British society. Dr Lord Rowan Williams achieved both positions, all the while producing high-quality academic work. Besides, he entered the popular imagination when he conducted the marriage ceremony of Prince William and Kate Middleton which had an estimated television audience of one billion people. He now plays the role of a leading public intellectual: his debate with Professor Richard Dawkins, the formidable Oxford professor and widely seen as the leader of the New Atheists in the world, has acquired legendary status and should be studied for style and content.

Williams held an office that has been at the center of English history. The clashes between the reigning monarchs and the archbishops attempting to preserve the primacy of the church are legendary. In the twelfth century, Henry II prompted the murder of Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral itself and Thomas Cranmer, who helped build a case for Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon, was executed in the sixteenth century, but not before he compiled the English Book of Common Prayer. Balanced against this, however, have been the many occasions when the church has reached across sectarian lines to embrace those of other faiths. Williams has done just this, and with substantial intellectual authority—he was described by a biographer as the most intellectually distinguished Archbishop of Canterbury since Saint Anselm who served in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. Furthermore, Williams’ influence and profile extends well beyond the boundaries of his own Church of England to include Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christianity.

Williams’ talents additionally include poetry, and he has published both books of his own poetry and a book of commentary on spiritual poems by Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists of different nationalities. He is fluent in around ten languages and his diverse intellectual influences include religious scholars like Thomas Merton and Meister Eckhart and philosophers like Ludwig Wittgenstein. Williams is a formidable theologian whose prodigious scholarship also effortlessly ranges across the fields of literary criticism, philosophy, and political theory.

I have seen up close Williams’ commitment to interfaith dialogue and embracing non-Christians over the years in my meetings with him. Dr Amineh Hoti and I were invited to Lambeth Palace in 2012, for example, to attend one of Williams’ final public events as archbishop—which notably focused on interfaith engagement—and I was asked to deliver the keynote address in the afternoon session. At this event, the lectures of the archbishop to Muslim audiences in Egypt, Libya and Pakistan, which had been compiled into a volume and translated into Urdu and Bengali, were presented to the archbishop along with glowing speeches made by Muslims recording the contributions of the archbishop in promoting interfaith dialogue. After the official events he still found time to meet Amineh and myself separately with his usual courtesy and kindness.

Williams has also been a great supporter of Amineh, coming to Cambridge to launch her book project Valuing Diversity: Towards Mutual Understanding and Respect at Michaelhouse, one of the oldest churches and educational centers in the UK. We returned to interview Williams a few years later during our fieldwork, this time at the

Concerning the UK, Europe and Islam, Lord Rowan said that Islam is not separate from Europe nor does it represent something alien, but it is within the European cultural sphere and context and tradition: “Islam has long been bound up with Europe’s internal identity as a matter of simple historical fact, and it stands on a cultural continuum with Christianity, not in some completely different frame.” The UK has been “affected by the strand of mathematical and scientific culture stemming from the Islamic world of the early Middle Ages…aspects of medieval Christian discourse took shape partly in reaction to Islamic thought. The apparently alien presence of another faith has meant that we have had to ask whether it is after all as completely alien as we assumed; and as we find that it is not something from another universe, we discover elements of language and aspiration in common”

Master’s Lodge at Cambridge’s Magdalene College. The image of Lord Rowan absorbed in a Rubik’s Cube with four-year-old Anah Hoti, Amineh’s daughter and my granddaughter, at this meeting reminds us of his human quality of compassion. He is known in the land as a champion of the less privileged and the voiceless. His Welsh background has helped him sharpen his empathy for the underdog—particularly minorities and those of different ethnicities and religions, and he has affirmed, “ God is likeliest to be found among those we have…dismissed or shut out.” In action, in belief, and in thought Lord Rowan has practiced Mingling. At the heart of his work and advocacy has been an embrace of the “Other,” which he argues creates the necessary space for mutual growth and enrichment based on encountering difference. His compassion lies close to the surface.

Williams’ efforts in this regard have not been without controversy, particularly as far as the Muslim community was concerned after 9/11, an event that he witnessed up close while serving as Archbishop of Wales (he was only a few blocks from the World Trade Center on that morning). To him, the importance of interfaith dialogue and facilitating human coexistence based in the message and example of Jesus only grew in importance after that horrible day. When it became known that Williams might soon become Archbishop of Canterbury not long after 9/11, he was described in the Wall Street Journal as a “terror apologist” for calling on people to understand the terrorists’ motives and making statements like “Bombast about evil individuals doesn’t help in understanding anything.”

Rupert Shortt, Rowan’s Rule: The Biography of the Archbishop of Canterbury (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdman’s Publishing Company, 2008), p. 3.

Shortt, Rowan’s Rule, p. 3.

Rowan Williams, A Century of Poetry: 100 Poems for Searching the Heart (London: SPCK, 2022).

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 71.

Rowan Williams, Choose Life: Christmas and Easter Sermons in Canterbury Cathedral (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), p. 187.

Peter Mullen, “Tales of Canterbury’s Future?,” The Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2002.

But this was nothing compared to the uproar that resulted from Williams’ 2008 lecture on sharia law, in which he argued that British law must take seriously the presence of populations such as Muslims who had their own legal interpretations, and he hoped to open up a space for conversation which might lead to a more plural legal system. The tabloid headlines included “WHAT A BURKHA: Archbishop wants Muslim Law in UK” and “ a victory for al Qaeda.” There were calls for his resignation as British government officials complained that Williams was trying “to fundamentally change the rule of law.” There was also criticism within the church, for example from bishops in Nigeria. Williams explained that he had only hoped to create “ a helpful interaction between the courts and the practice of Muslim legal scholars in this country.” His commitment to serious interfaith dialogue, not just in the theological or educational realm but in the practical, nuts and bolts aspects of living together and what this means and looks like, was undiminished by the controversy.

Williams was born in 1950 in Swansea, Wales to a middle-class family. He was descended from Welsh miners and shepherds who were drawn into the Swansea valley at the beginning of the nineteenth century, hoping to find greater opportunities. His family was proud of their Welsh identity, and while Williams grew up speaking both Welsh and English, his grandfather had banned the use of English in their home. As an infant Williams was stricken with meningitis, and he was unable to play sports or engage in physical activities in the way that most boys did. Consequently he withdrew into the world of books, consuming works of literature, philosophy, and history. He went on to attend the University of Cambridge and while he initially planned to attain a degree in English literature, he switched to theology. This was not, as he saw it, an alternative to literature but “as a way of exploring the deeper questions that he had stumbled upon in his reading of authors like Shakespeare, T. S. Eliot, and W. H. Auden.”

Williams’ reaching out to the “Other” was already visible during this period in his interest in Russian Orthodox Christianity. It was not an interest that would have necessarily been viewed with neutrality by others around him, as this was the height of the Cold War in the 1960s. As a teenager, Williams became aware of what he called “an alien cultural presence on the other side of Europe which had a hinterland of imagery both odd and seductive” and he wished to know more. He read Russian literature, listened to Slavic music, and watched Russian films. After graduating from Cambridge, he moved to Oxford where he completed a PhD on the Russian theologian Vladimir Lossky.

Williams was ordained as a deacon and spent nearly a decade in parish work in Cambridge, all the while continuing his academic career. He then moved to Oxford to assume the post of Professor of Divinity and Canon of Christ Church, and subsequently ascended to the high church positions of Bishop of Monmouth and Archbishop of Wales before becoming Archbishop of Canterbury in 2002. At his enthronement as archbishop, he gave an address which outlined his approach throughout his tenure at embracing the “Other”: “Once we recognize God’s great secret, that we are all made to be God’s sons and daughters, we can’t avoid the call to see one another differently. No one can be written off; no group, no nation, no minority can just be a scapegoat to receive our fears and uncertainties. We cannot assume that any human face we see has no divine secret to disclose,” including “those who are culturally or religiously strange to us.”

In his writings and teachings, Williams has stressed both the inherent diversity of the world and our essential connections with this diversity. We should accept, he says, that the “diversity and mysteriousness of the world around is something precious in itself. To reduce this diversity and to try and empty out the mysteriousness is to fail to allow God to speak through the things of creation as he means to.” We are all intermeshed and should recognize “the complex interrelations that make us what we are as part of the whole web of existence on the planet.” Humanity itself is “unimaginable without all those other life forms which make it possible and which it in turn serves and conserves.” We should be aware that “we can’t control the weather system or the succession of the seasons. The world turns, and the tides move at the drawing of the moon. Human force is incapable of changing any of this. What is before me is a network of relations and interconnections in which the relation to me, or even to us collectively as human beings, is very far from the whole story. I may ignore this, but only at the cost of disaster.”

And yet, we have a tendency to not recognize this interconnection, to think of ourselves as somehow meaningful or complete either on our own or as part of our own group. But this is to lack a perspective of the whole. “To understand the world,” Williams contends, “is to sense a deep embrace, a mutuality or interpenetration

The Queen and the archbishop leave Lambeth Palace, London, followed by the Duke of Edinburgh and Jane Williams, after attending a multi-faith diamond jubilee reception, February 2012. In our interview with him, Williams closed with the following hopeful prayer which captures his own faith and optimism that the peoples of the world may be brought together in love and peace: “May God our Creator open our hearts and our ears to one another. And may God our Creator whose will is for our peace and our wellbeing lead us hand in hand towards a true worldwide community in which none is forgotten, none is oppressed, none is humiliated. May God our Creator teach us to value and to revere the signs of His presence in each one of us, so that in all things there will be the peace and reconciliation that our Lord God requires. Amen.”

that does not simply negate the reality of individual subjects or individual moments, but forbids us from thinking of those moments as enclosed or absolute.”

A good example of Williams’ thinking on this subject can be seen in his statements on nationalism. He is not against being proud of one’s own ethnic identity—in his case being Welsh. But we must always keep in mind the link with the greater unity. Each group of “people living with this or that corporate history, common language and culture” such as the Welsh, he argues, should see their identity “as a thread in a larger tapestry.” This idea is firmly rooted in Christian theology and history, Williams argues, and “Any racial group or language group or sovereign state whose policy or programme it is to pursue its interest at the direct cost of others has no claim on the Christian’s loyalty.”

This perspective comes out clearly in Williams’ commentary on the Welsh poet Waldo Williams, whose verse, “Cadw ty mewn cwmwl tystion” (“Keeping house/ among a cloud of witnesses), Wiliams notes, “has become almost proverbial in Wales.” The line captures the Minglers’ view of embracing local and universal simultaneously, as Lord Rowan explains, “Belonging to a tradition with deep local roots makes us heirs to not a possession that has to be violently defended but a security which allows us to seek mutual recognition between people, not opposition and rivalry.”

Our identities as a part of a group, then, should never be seen as closed but open—especially to the “Other.” In our interview with Lord Rowan, he told us, “Identity is always something we have to work at. It’s not something just given. We can’t simply say, ‘This is who I am. It’s all in here. In me, or in us, and that’s all we need to know.’ The identity of Britain, or just England, of course, has always been diverse. And I’m speaking here as somebody who comes from a minority group in Britain, that is the Welsh, with their own language, their own cultural history. So, I suppose I’ve been conscious from my childhood that it’s more than one story. And that’s the second thing about identity. We find out who we are by telling stories about ourselves.” In his case, “When I was at school, we were obliged to study Welsh history as well as English. So, it was like having binoculars. Two things to look at.”

The “Other” is crucial for Williams because they bring out something important in us—essentially, we find out who we really are while meeting one another, learning about each other, and going on a journey together. As Williams says, “We shall none of us know who we are without each other.” While we may believe that our own

Shortt, Rowan’s Rule, p. 396.

Benjamin Myers, Christ the Stranger: The Theology of Rowan Williams (London: T & T Clark, 2012), p. 63.

Myers, Christ the Stranger, p. 63.

Shortt, Rowan’s Rule, p. 396.

Shortt, Rowan’s Rule, p. 400.

Shortt, Rowan’s Rule, p. 26.

Myers, Christ the Stranger, pp. 13-14.

Myers, Christ the Stranger, p. 14.

Myers, Christ the Stranger, p. 22.

Shortt, Rowan’s Rule, p. 65.

Shortt, Rowan’s Rule, pp. 260-261.

Williams, Choose Life, p. 55.

Williams, Rowan Williams, Faith in the Public Square (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), p. 201.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 198.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 185.

Williams, A Century of Poetry, commentary on Jan Zwicky, “Grace Is Unmoved. It is the Light that Melts, excerpt from ‘Philosophers’ Stone.’”

Rowan Williams, On Christian Theology (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), p. 254.

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 253.

Williams, A Century of Poetry, commentary on Waldo Williams, “What is Man?”

Williams, A Century of Poetry, commentary on Waldo Williams, “What is Man?”

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 303.

experience is the correct one or only one that matters, “The individual reality or situation is like a single chord abstracted from a symphony: it can be looked at in itself, but only with rather boring results, since what it is there and then is determined by the symphony…there is no perspective outside plurality.” He calls for us to turn “away from an atomized, artificial notion of the self as simply setting its own agenda from inside towards that more fluid, more risky, but also more human discourse of the exchanges in relations in which we’re involved.” He wants us to be “confident enough to exchange perspectives, truths, insights.” Of great importance is “listening” to others, which is needed “almost more than anything else…patience before each other, before the mysteriousness of each other.”

In reaching out to the “Other,” we deemphasize the self and thus create a better world for all—including ourselves: What is important is “life for the other, which is the life that Christ embodies, in history as in preaching and sacrament.” Williams affirms that “What we need in order to live in a balanced, ‘reasonable’ way within creation is the well-being and flourishing of our neighbours, justice being done to and for them.” He explains, “Scripture is definitely clear that to be drawn near to God is always to be drawn near to each other, and there is no way of separating those two.” If we do the opposite, as so many do, if we “live untouched or uncaring in the midst of poverty, disease, violence, corruption and disaster, we starve. Our failure in giving to the neighbour becomes an injury to ourselves.” We also often fall prey to “zero-sum” thinking which “assumes that there can never be ‘enough to go round’: if I have more, they have less; if they have more, I have less” which is “so evidently at the root of virtually all major conflicts, social, national and political as much as personal.”A perspective of unity, however, gets beyond such zero-sum thinking and can promote peace.

The essential basis of our relations with all is love, Williams notes, which was Jesus’ example, as Jesus advocated for the “harmony and well-being of the entire human family.” To follow Jesus’ example is “to be open to all the fullness that the Father wishes to pour into our hearts…humanity in endless growth towards love.” Just as God loves all, “we too must learn to love beyond the boundaries of common interest and natural sympathy and, like God, love those who don’t seem to have anything in common with us.” He further asserts that “Creation, the total environment, is a system oriented towards life—and, ultimately, towards intelligent and loving life.” Lord Rowan is insistent that “There cannot be a human good for one person or group that necessarily excludes the good of another person or group” and “no life can be allowed to fall out of the circle of love.” On the basis of this love—the love on which the “universe” is founded—will society and the world flourish.

Williams also argues that just as truth cannot be encapsulated in one’s own limited perspective without encountering the “Other,” no one religion can be so contained—the divine is much larger than any single experience, comprehension, or tradition. Concerning Christians, he cites the French Catholic theologian Jacques Pohier, who said, “God does not show himself in Jesus Christ as being the totality of meaning.” This means, Williams contends, that everyone is trying to understand God in their own ways, and God “does not control how the divine is to be met by means of a single set of revealed schemata.” “We do not, as Christians,” Williams explains, “set the goal of including the entire human race in a single religious institution, nor do we claim that we possess all authentic religious insight. Being Christian “is believing the doctrine of the Trinity to be true…It is not to claim a totality of truth about God or about the human world, or even a monopoly of the means of bringing divine absolution or grace to men and women.”

Once again, as a Mingler, Williams is calling our attention to a larger reality which unifies us. While, “we are, by the very nature of our humanity, naturally attuned to the reality of God,” he argues, the particular ways in we understand God will differ. This is where interfaith dialogue can be very fruitful, because “we have none of us received the whole truth as God knows it; we all have things to learn.” Williams asserts that “there is no possibility of claiming that every human question is answered once and for all by one system.”

Prince William of Wales , Lord Rowan Williams , and Catherine Princess of Wales

Williams’ approach to interfaith thus starts from a position of “humility” which asserts that “even as we proclaim our conviction of truth,” we “acknowledge with respect the depth and richness of another’s devotion to and obedience to what they have received as truth.” This does not imply “for a moment that dialogue entails the compromise of fundamental beliefs or that the issue of truth is a matter of indifference; quite the opposite.” It is likewise not a matter of “the triumph of one theory or one institution or one culture,” but how we can constructively “find a way of working together towards a mode of human co-operation, mutual challenge and mutual nurture.”

Williams goes even further and gives us a concrete and practical program for how to conduct interfaith dialogue. He counsels us to avoid misunderstandings by paying close attention to the language and concepts we employ, asking questions like “Are these two or more traditions addressing similar or different concerns when they use language and imagery that seems to be closely similar?” When we begin to understand another tradition on its own terms, things that we initially thought might be the opposite of what we believe turn out not to be so. Then you can “try to discover what your own tradition commits you to and how it answers legitimate criticism from outside—criticism which often (as in the case of the mutability of God) could be raised intelligibly within the native tradition. What emerges is frequently a conceptual and imaginative world in which at least some of the positive concerns of diverse traditions are seen to be held in common.”

We are already often operating at a disadvantage when we attempt dialogue between faiths and cultures because of the images that we often have of the “Other.” Frequently, Williams states, the “Other” is constructed as the “opposite” of the “Self.” This distorted “Other” is often a “fantasy” to us—an act of “conscription” into our “story,” without caring to understand their story from their own point of view. It is a universal problem as “all human beings are liable to be drawn into the fantasy lives of others.” This, however, is destructive, with Williams explaining, “When you get used to imposing meanings in this way, you silence the stranger’s account of who they are; and that can mean both metaphorical and literal death.”

This has been done often by Christians, Williams says—they “conscripted Jews into their version of reality and forced them into a role that has nothing to do with how Jews understand their own past or current experience.” Speaking of the resulting anti-Semitism, Williams told us, “The poison is still in the system. And even now, even today.” It is also the case with Muslims, who “were made to play a part in the drama written by Christians, as a kind of diabolical mirror image of Christian identity, worshipping a trinity of ridiculous idols.” Jews and Muslims, for their part, “cherished equally bizarre beliefs about Christianity at times. They, like us, needed to assert some kind of control over the stranger, the other by ‘writing them in’ in terms that could be managed and manipulated.”

In the contemporary world, Williams lamented, this is happening far too often. We fear one another, and thus build walls between us, but “Every wall we build to defend ourselves and keep out what may destroy us is also a wall that keeps us in and that will change us in ways we did not choose or want. Every human solution to fears and threats generates a new set of fears and threats…Defences do some terrible things to us as well as to our real and imagined enemies.” We also often see ourselves as victims of an “Other” which feeds into our opposition of them. This sense can become “so entrenched that even one’s own power, felt and exercised, does not alter the mythology.”

How do we get past our fantasies of the “Other” which can be so dangerous? Once again, Lord Rowan presents several practical steps. First, he calls for “abandoning the right to decide who they [strangers] are.” Instead, we should be “enabling the stranger to be heard, deciding that the stranger has a gift and a challenge that can change you.” Second, is to acknowledge our inherently limited view. Williams states, “I recognize that what’s before me, whether rose or person, can be seen from other perspectives than mine.” In being open enough to listen, we will also learn how we are seen—we will discover “things about ourselves we did not know, seeing ourselves through the eyes of another.”

Thirdly, rather than trying to learn about the “Other” by focusing only on theology or beliefs, spend time with them. Williams recommends, “hang around with the representatives of one or another religious tradition—share the experiences of worship, entertain the images, the stories they tell. Look at the lives they point to as important lives, important saints, figures in their tradition: because I think it is profoundly true that the religious apprehension is caught, not taught.”

This was the element he emphasized in his interview with us, stating, “When you realize you’ve not really got close to your neighbors, you will either panic, or you can say, ‘well it’s time I started isn’t it?’ So, either you react with projecting all sorts of mysterious and terrible things on to them or you sit with them and listen.” In the case of Muslims, Williams said, “We in Europe and elsewhere simply need to educate ourselves about what Islam really is. And we need to listen very hard to the average Muslim neighbor…To listen to the experience of those who are unobtrusively but faithfully living ordinary Muslims lives fully within our society. Listen to them.”

The fourth step, in a recommendation also endorsed by Minglers such as Rumi, is to attempt to see others who you may not like from the perspective of those who love them. You will then see them as full human beings and it becomes more difficult to hate and dehumanize them. The final step is to acknowledge that others have suffered. In that sense, tragedy can provide an opportunity because it can enable you to empathize with others. This was Williams’ message when he spoke at a church in New York on September 12, 2001: “trauma can offer a breathing space; and in that space there is the possibility of recognising that we have had an experience that is not just a nightmarish insult to us but a door into the suffering of countless other innocents, a suffering that is more or less routine for them in their less regularly protected environments…There is a global hospitality possible too in the presence of death.”

Another aspect of Lord Rowan’s thought important for our discussion of Mingling is his political philosophy. Like philosophers such as Plato and Socrates, Williams has spent a great deal of time pondering the ideal society. For him, in accordance with his Christianity and outlook on the “Other,” the ideal society is a plural society. It is a place where everyone can be themselves, where they bring their own unique contribution to public life and learn from each other. In this, he is engaged in a similar project and is in dialogue with UK Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, another one of our Minglers who also attempted to put forth a model of the ideal society based in the high aspirations of his own religious community.

Williams, On Christian Theology, p p. 186-187

Rowan Williams, Being Human: Bodies, Minds, Persons (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2018), p. 47.

Williams, Being Human, p. 40.

Rowan Williams, Where God Happens: Discovering Christ in One Another (Boston: New Seeds, 2005), p. 84.

Rowan Williams, Christ: The Heart of Creation (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), p. 195.

Rowan Williams, Passions of the Soul (London: Bloomsbury, 2024), p. 44.

Shortt, Rowan’s Rule, p. 219.

Williams, Passions of the Soul, p. 44.

Williams, Passions of the Soul, p. 66.

Williams, Christ, p. 220

Rowan Williams, Holy Living: The Christian Tradition for Today (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), p. 95.

Williams, Passions of the Soul, p. 107.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 205.

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 230.

Williams, Choose Life, p. 38.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 232.

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 122.

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 122.

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 194.

Williams, On Christian Theology, pp. 196-197.

Williams, Where God Happens , p. 49.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 301.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 299.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 301.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 301.

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 191

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 191

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 131.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 290.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 287.

Rowan Williams, Writing in the Dust: After September 11 (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002), p. 68.

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 297.

Williams, Writing in the Dust, p. 64

Williams, Writing in the Dust, p. 63

Williams, Writing in the Dust, p. 63

Williams, Writing in the Dust, p. 63

Williams, Choose Life, pp. 44-45.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 144.

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 303.

Williams, On Christian Theology, p. 305.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 17.

Williams, Choose Life, p. 156.

Shortt, Rowan’s Rule, p. 125.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 17.

Williams, Writing in the Dust, p. 60.

Williams posits the ideal society on two main levels, the level of the nation or state and the level of the world. The same general elements are present in both. Williams’ ideal nation-state and world alike is a place in which people from different groups are able to recognize, communicate with, trust, and respect one another, and have conversations and debates “ across cultures about the requirements of the good.”

In the state, he explains, there will always be different communities and groups, each with their own concerns, their own unique worldviews, their ways of running their own affairs and so on. Williams argues that every group should have their utmost rights and abilities to do so. But his model is not the “multicultural” one discussed in the West which, he contends, can isolate communities and in which the state can become “chaotically pluralist, with no proper account of its legitimacy except a positivist one (the state is the agency that happens to have the monopoly of force).’” Nor is it the secular model, which seeks to push difference, especially religious difference, into the private realm and to remain “neutral” in public. If religions are not brought into the open, Williams believes, “the most important motivations for moral action in the public sphere will be obliged to conceal themselves. And religious identity, pursued and cultivated behind locked doors, can be distorted by its lack of access to the air and the criticism of public debate.”

So, we are forced to deal with each other, and the gifts and results of the encounter are substantial. “Forget ‘multiculturalism’ as some sort of prescription,” Williams urges, “begin from the multicultural fact. We are already neighbours and fellow-citizens; what we need is neither the ghetto nor the reassertion of a fictionally unified past, but ordinary intelligence, sympathy and curiosity in the face of difference—which is the basis of all learning and all growing-up, in individuals or societies.”

Once we are aware of others’ differences, we will discover what elements we share and which we may not. As far as the politics of the state itself, the political process should be to identify those “transcendent values” we discover in the process of dialogue that we all have in common, those “values and priorities” which “can claim the widest ‘ownership.’” This can be a particular moral vision or something as practical as paved roads. Other examples include development programs for a city or region, environmental regulations, and questions of bioethics.

The goal is to hold state-level discussions and pass laws concerning how everyone can live together, dealing with issues of common interest that are beyond the level of the individual or a particular group. But the state can only be the desired “space in which distinctive styles and convictions could challenge each other and affect each other” if members of each group first have “the freedom to be themselves.” In the end, “ what is needed for our convictions to flourish is bound up with what is needed for the convictions of other groups to flourish. We learn that we can best defend ourselves by defending others.” He calls for “ a model of politics which is always to do with negotiation and the struggle for mutual understanding.”

Williams endorses Jonathan Sacks’ belief that society can best function as a “covenant,” a resonant concept in Judaism and Christianity. As Williams explains, “Diverse communities resolve to enter a kind of ‘covenant’ in which they agree on their mutual attitudes, and thus on a ‘civil’ environment, in every sense of the word; and they build on this foundation a social order in which all have an investment.”

One important role for the state—and other groups and entities—in Williams’ vision is in education, particularly in educating students about each other’s traditions and discussing the important links between them in the past. He says, “A society in which religious diversity exists is invited to recognize that human history is not one story only; even where a majority culture and religion exists, it is part of a wider picture.” History shows that “diversity cannot help being interactive; and that it in itself can prompt us to think of social unity as the process of a constantly readjusting set of differences, not an imposed scheme claiming totality and finality.” History is key because “if we don’t know how we got here, we will tend to assume that where we are is obvious. If we assume that where we are is obvious, we are less likely to ask critical questions about it.”

State education should highlight the ways in which religious traditions interact in history and how they arose together. The reality is that “divergent strands of human thought, imagination and faith can weave together in the formation of each other and of various societies” and this is just what has happened, for example, in the UK. The country and culture are the product of many different influences, Williams told us, for example, “we’ve always had waves of immigrants. In fact, the English themselves are a wave of immigrants from the point of view of the Welsh.” Concerning the UK, Europe and Islam, Lord Rowan said that Islam is not separate from Europe nor does it represent something alien, but it is within the European cultural sphere and context and tradition: “Islam has long been bound up with Europe’s internal identity as a matter of simple historical fact, and it stands on a cultural continuum with Christianity, not in some completely different frame.” The UK has been “affected by the strand of mathematical and scientific culture stemming from the Islamic world of the early Middle Ages…aspects of medieval Christian discourse took shape partly in reaction to Islamic thought. The apparently alien presence of another faith has meant that we have had to ask whether it is after all as completely alien as we assumed; and as we find that it is not something from another universe, we discover elements of language and aspiration in common.”

Williams put it this way while speaking with us: “The history of Andalucia and the interaction of Jewish, Muslim, and Christian communities there, that’s very well known. I’d also point out the enormously important cultural phenomenon of Sicily. Right in the heart of the Mediterranean world, where you have the Norman culture of Northern Europe coming in, you have the Byzantine culture of Eastern Europe present, and you have a North African and Arab-speaking element. And through most of the Middle Ages Sicily was, again, a place of conversation. And look at Eastern Europe. You may say that the Eastern Empire, the Byzantine Empire was locked in conflict with the Islamic world, and of course it was. At the same time, it was also interacting constantly with it, more than with the West at times. Even intermarrying with it.” Thus, the reality of our current situation where we are living with so much diversity “becomes a stimulus to find what it is that can be brought together in constructing a new and more inclusive history,” and “The fuller awareness of a shared past opens up a better chance of shared future.” Education should stress these kinds of past connections between communities that helped create the society of the present.

The same principles that hold true for the ideal state also hold for the ideal world. Just like the state, the world has diverse peoples and, in our current system, states which have sovereignty. There is a need for a world body to bring the different groups together in the common interest—especially at promoting agreed-upon rules and norms. Williams explains, “Just as the particular state has the task of addressing issues that no one community can tackle, so in the global context there are issues beyond the resource, the competence or the legitimate interest of any specific state.” This is particularly crucial concerning the mediation of disputes between countries and issues like climate change, environmental degradation, water access, and controls on deforestation and overfishing. There are issues that affect “ the security of any imaginable political and social environment, safeguards without which no individual state can realize its own conception of the good.” Additionally, “The unchallenged dominance of one national interest will always need restraining.”

Williams is clear that he is not arguing for a kind of “world government” that dictates terms to individual countries. He is proposing that matters be decided on different levels—a local level, a state level, and ultimately those matters that concern all states and peoples should be discussed at a world level. We must always work to perfect international institutions, to prevent them from “micromanagement” on cultural or economic issues of individual states or from majorities enforcing “their group interests on particular states.”

In his interview with us, Williams discussed his ideas for a UN-level global body that could specifically mediate between peoples in the key areas of concern that arise around the world: “In addition to a United Nations Security Council, perhaps we need a United Nations Mediation Council. Perhaps we need a few a states with a reasonably good political track record who could be relied on to do some of the brokerage of peace agreements and so forth between communities in tension.”

Like the other Minglers, Lord Rowan embodies a profound optimism and faith of conviction even in difficult times. He articulated this sense powerfully in a rumination on visiting South Africa under apartheid. Speaking of the courage of a Black South African church worker he met named Helen, who was interrogated by the secret police after Williams departed, he asked, “Is it possible for human beings—especially in circumstances of pressure and oppression like that—to look at something other than just the power and violence that is around them? Is there freedom even in the middle of an experience like that?... Is there somewhere else to go? Is there something else to see? Is there another world? ‘Other world’ may conjure up images of fairies, spirits and ghosts but I hope [Helen’s story] may show what it is to live in another world and at the same time to live right in the middle of this one; to live with another vision; to step to a different drummer...because that is the heart—the hard essence of faith.”

In our interview with him, Williams closed with the following hopeful prayer which captures his own faith and optimism that the peoples of the world may be brought together in love and peace: “May God our Creator open our hearts and our ears to one another. And may God our Creator whose will is for our peace and our wellbeing lead us hand in hand towards a true worldwide community in which none is forgotten, none is oppressed, none is humiliated. May God our Creator teach us to value and to revere the signs of His presence in each one of us, so that in all things there will be the peace and reconciliation that our Lord God requires. Amen.”

Akbar Ahmed is Distinguished Professor and the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies, School of International Service, American University, Washington, DC, and Wilson Center Global Fellow. He was described as the “world’s leading authority on contemporary Islam” by the BBC. Among his many books are his quartet of studies examining the relationship between the West and Islamic world published by Brookings Institution Press: Journey into Islam (2007), Journey into America (2010), The Thistle and the Drone (2013), and Journey into Europe (2018).

Frankie Martin is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Anthropology at American University. He was senior researcher for Akbar Ahmed’s previous quartet of Brookings Institution Press studies on the relationship between the West and Islamic world and holds an MPhil in Anthropology from the University of Cambridge. His writing has appeared in outlets including Foreign Policy, CNN, the Guardian, and Anthropology Today.

Dr Amineh Ahmed Hoti is Fellow-Commoner at Lucy Cavendish College, University of Cambridge and Governor, St. Mary’s School, Cambridge. She was also a senior researcher for Akbar Ahmed’s quartet of Brookings Institution Press studies on Western-Islamic relations. She received her PhD from the University of Cambridge and co-founded and directed the world’s first Centre for the Study of Muslim-Jewish Relations at Cambridge. Her most recent book is Gems and Jewels: The Religions of Pakistan (2021).

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 123.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 80.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 53.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 112.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 296.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 297.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 81.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 297.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 297.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 300.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 299.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 299.

Williams, Being Human, pp. 56-57.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 300.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 71.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 300.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, pp. 299-300.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 300.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, pp. 53-54.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 55.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 56.

Williams, Faith in the Public Square, p. 56.

Shortt, Rowan’s Rule, p. 119.