Reminiscences from a Quarter-Century

By Dr Syed Amir

Bethesda, MD

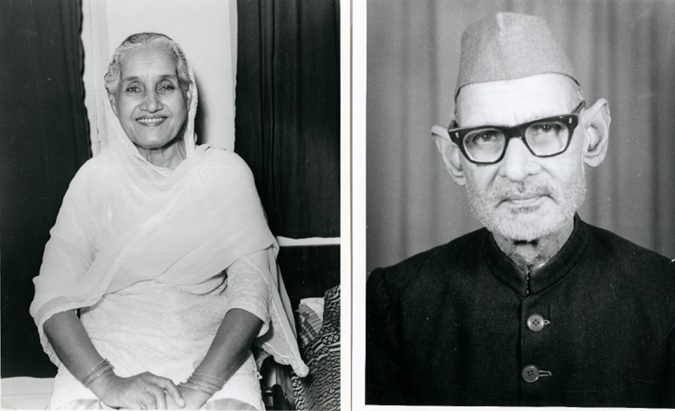

January 2025 marked a quarter century since my father died in Karachi, Pakistan, of what would be considered old age. He was in his early nineties. While he physically deteriorated, his mental faculties remained unimpaired almost until the end. The anniversary of his death brought back a surge of memories. Hakim Syed Abdul Qavi was born and spent most of his life in Sahaswan, a small town in Uttar Pradesh, India, where my ancestors lived for five centuries.

My father became an orphan early, and his mother, a woman of unusual strength and foresight, took control of the household and the upbringing of her three young children. Growing up, my father followed the profession of his father and grandfather. He was trained as a hakim, or practitioner of the Unani system of medicine at Tibbia College, Delhi. The institution was founded by the celebrated Hakim Ajmal Khan, an iconic nationalist leader. Hakim Ajmal Khan felt strongly that the Tibb-e-Unani had not kept pace with the progress in medicine and needed to be modernized. The teaching and syllabus in the College were updated to incorporate some modern diagnostic techniques.

In India, the Unani system reached its zenith during the Muslim period, when the kings and their courtiers employed medical practitioners who played dual roles. In addition to tending to their health and sickness, they provided sage advice to the sovereign. Delhi had several celebrated Hakims in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and their fame attracted patients from all corners of the country. This was an era before the advent of modern diagnostic techniques. Some of the Hakims had refined their techniques to diagnose illness by relying on their physical examination, keen sense of observation, touch, and deductive faculties. Some were even credited with mystical talents, enabling them to diagnose illness by merely feeling and listening to the patient's pulse. The princely rulers were their frequent clients who needed potions for rejuvenation, especially restoration of their waning sexual powers.

When my father set up his medical practice in the first quarter of the twentieth century, he was one of the few medical providers in our hometown. There was one government hospital, but it was in poor shape and seldom staffed or equipped. The town had no electric power, telephone, or running water. Newspapers, the only source of information, arrived a couple of days late. The streets were lit nightly by ineffective kerosene lamps that went out before midnight. The roads were usually quiet at night, as people had no reason to come out. My father established himself as a compassionate Hakeem and became known for his skills as a physician. Many depended on him to attend to their families' illnesses.

Sahaswan had no transportation system, so people just walked to wherever they wanted to go. One of my childhood memories is the knock at our door in the dead of a wintry night when someone sought help from my father for a sick family member. Father never hesitated to go to attend to the patient, however late the hour. He walked, guided by the caller, who carried a paraffin lamp in one hand and a stick in the other. The streets were completely safe, and the stick was to avoid potholes and scare nocturnal creatures that abounded in rural areas.

Whenever he had to visit a patient in a nearby village, he depended on a bullock cart. Occasionally, when a wealthy landlord became ill and sought help, an elephant would show up at my father’s clinic to carry him to the patient. Whenever it happened, it was an exciting spectacle for children like me, who gathered around it, its arrival heralded by jingling bells. Nobody had a car in those days, and owning an elephant symbolized wealth.

My father remained a vegetarian for most of his life. He believed in the benefits of fasting and liberally prescribed it to his patients. He also practiced it himself whenever he felt unwell. He had never used Western medicine for most of his life and trusted his own herbal remedies, which served him well.

My father was active in India’s freedom movement as a member of the Indian National Congress and admired Maulana Azad, Mahatma Gandhi, and Pandit Nehru. I recall pictures of the three leaders hanging in his clinic. Later, he became an enthusiastic supporter of the Pakistani movement and, after completing my education at Aligarh Muslim University, encouraged me to migrate to Pakistan, where most of my relations had already settled. Later, on my return from England after my graduate studies, my parents migrated to Pakistan to live with my wife and me. It was a happy three-year period that I cherish greatly.

When we left for the US, my parents were living independently in their own flat, close to my sister and other relatives. Father loved Pakistan but felt lonely in the final years of his life. He displayed great fortitude and acceptance of the divine will when my mother died some ten years before him and even more so when my older sister died in India at a relatively young age. On one of my last yearly trips to see him, I heard him say for the first time that he missed Sahaswan, our hometown. By that time, almost all of his contemporaries were deceased, many of whom were migrants to Karachi like him and had often come to visit him.

As I reach my own advanced age, I am reminded daily of what life is like if one is blessed with a long life. Most friends and close relatives with whom I shared life’s experiences, sorrows and joys, have now departed. It is no longer possible to reminisce about events or share memories of a bygone era when life was so different, so uncomplicated. The time now seems to pass at a breakneck pace. Fortunately, I can draw much pleasure and comfort from younger friends who bring a different perspective on life and afford invaluable companionship. There are many former students of Aligarh Muslim University in the Washington area and a very active Aligarh Alumni Association. They organize social, cultural, and literary events, a milieu that significantly benefits many of us.

For many years, the Association has held a yearly international Mushaira that has attracted many iconic poets from the subcontinent and has become its signature event. Our area is also blessed with a weekly Saturday Zoom program organized by an Aligarh alumnus, Dr Raziuddin, who draws a broad spectrum of speakers from around the globe.

I want to close this essay with the sagacious advice that the former US First Lady Barbara Bush gave in her 1990 commencement address to Wesley College graduates in Boston: "At the end of their lives, they would never regret not taking one more test or closing one more deal but would regret not spending more time with a husband, a child, a friend, or a parent." The advice is as pertinent today as it was 35 years ago.

(Dr Syed Amir is a former assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and a retired health scientist administrator at the US National Institutes of Health)