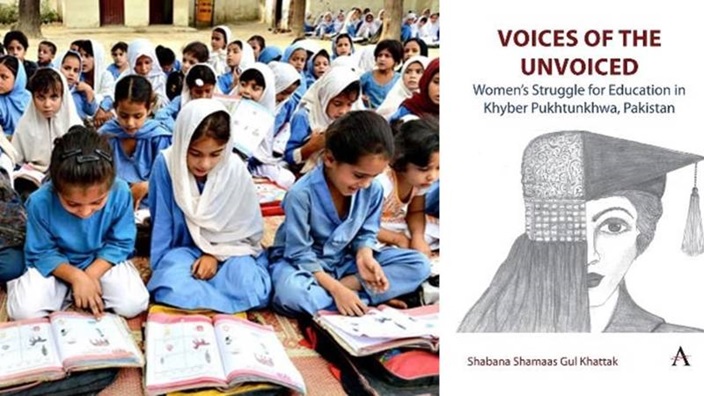

Pushing the Frontier for Women: Shabana Khattak’s Struggle for Education in KP

(Foreword to Shabana Shamaas Gul Khattak’s "Voices of the Unvoiced: Women’s Struggle for Education in Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Pakistan")

By Dr Akbar Ahmed

American University

Washington, DC

Dr Shabana Shamaas Gul Khattak is the proud daughter of a proud and noble people. Her tribe, the Khattak, belongs to one of the largest and most celebrated ethnic groups in the world, the Pakhtuns. They live in one of the most inaccessible areas of the world, yet in terms of geo-political location a vital region of Asia. The Pakhtuns have produced ruling dynasties and in modern times Presidents of major nations like India and Pakistan.

The region has invariably attracted high-quality writing. From the very start of the British-Pakhtun encounter, there was the detailed study by Mountstuart Elphinstone. Other colonial officers fascinated by the Pakhtun wrote monographs that have lasted, and these include names like Sir Evelyn Howell and Sir Olaf Caroe. There were of course novelists writing about this area and its people. Rudyard Kipling’s Kim features a dashing if stereotypical Pakhtun horse trader and the novels of John Masters feature Pakhtun tribesmen.

After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, this region continued to attract fine writers. Leading anthropologists like Frederick Barth, Andre Singer, and Charles Lindholm contributed to Pashtun studies. There is the popular Pashtun Tales from the Pakistan-Afghan frontier by Aisha Ahmad and Roger Boase. Sahibzada Riaz Noor and Ijaz Rahim, two outstanding officers and poets, have written extensively on the people and area. Another civil servant, Gulam Qadir Khan Daur has written a powerful book on his tribe in Waziristan.

In spite of limited access to educational facilities and living in a patriarchal society, the area has also recently produced some high-quality scholarship by female Pukhtuna associated with the region. Dr Amineh Hoti obtained her PhD from Cambridge University, studying Yusufzai women in Swat and Mardan, Dr Faryal Leghari recently got her PhD from Oxford University based on her work in Waziristan. Amineh is the great-granddaughter of the Wali of Swat and Faryal’s mother was from Mardan. Malala Yusufzai, whom Dr Khattak so admires, is also from Swat and has written and spoken extensively about the area.

Dr Khattak’s book is as much autobiographical as it is sociological. She recounts her struggles to pursue education despite the hurdles she faces. Dr Khattak was born and raised in Akora Khattak in the Pakhtunkhwa province once called the North-West Frontier Province under the British. She later obtained her MA in education in London and her Doctorate in Gender, Islam, and Education from Middlesex University, also in London. She found that her province is dominated by culture rather than the teaching of Islam. There are pressures from even within the family that discourage her. But it is her father who stands by her and supports her, instilling pride in her people and dreams to contribute to the understanding of their culture. Behind these heroic female figures, we note there are usually heroic parents. These fathers and mothers take a stand to support their children against the tide of local normative opinion. For his courage, imagination and faith it is a good opportunity to salute Shamaas Gul Khattak, the father of our author Dr Khattak.

In spite of limited access to educational facilities and living in a patriarchal society, the area has also recently produced some high-quality scholarship by female Pukhtuna associated with the region

Dr Khattak herself has expressed gratitude to her father in a moving dedication to him:

“Dedicated to my great feminist father (Shamaas Gul Khattak), my first love, my inspiration and my strength, my Sonerine supporting me lovingly throughout my life.”

Inspired by her father’s support and fired by the examples of the legendary Malalai who died fighting the British and Malala Yusufzai, named after the Afghan heroine, Dr Khattak had her role-models. Dr Khattak would like every woman in the region to have the courage and the capacity to express herself like these legendary women. Indeed, there is an entire chapter called “Giving Voices to the Unvoiced” (Chapter 5). In her arguments, she points to the weakness in the position of what she called the secular feminists and emphasizes the importance of Pakhtun culture in the process of creating character and resistance.

Much of Dr Khattak’s ethnography comes from the Swat state. She dedicates an entire chapter to it called the “Historical perspectives of women’s education in the princely Swat State” (Chapter 2). She has given samples of her excellent interviews as appendices. We hear the voices of ordinary women and are moved by their courage and imagination against what seem insurmountable economic and political challenges. These women are determined to succeed. We get a glimpse of the Mullah who for a short while dominated Swat and mobilized the women of the region to support him. The book thus offers great ethnography providing a resource for further research.

Dr Khattak sees her own role as what she terms an “in-between.” She locates herself consciously between East and West. She is from the East, but she is educated in the West. Through the sea of Western theories, which include Marxism, feminism, etc. she finds strength and direction in her own cultural moorings. Her in-between position thus becomes not a source of ambiguity and uncertainty but one of strength and stability. The book clearly and strongly lays out a charter for Pakhtun women’s educational struggle in Pakhtun society. It is a call for action. The goal is emancipation and empowerment. Dr Khattak argues that the patriarchy of society and its militarization have been used as a tool for cultural governance of identity and gender stratification. She aims to synthesize feminist theories in a non-Western setting. She believes that it is the patriarchy that is so embedded in local society which is the main cause of the marginalization of women. It laid the grounds for the emergence of the Taliban and their ban on women’s education in the name of Islam in the Swat Valley. To her, the answer is education through which she wishes to affect change in society. The book is replete with scholarly references and comes with maps and appendices.

In the success that Dr Khattak has achieved, and so clearly against great odds, she has emerged as a heroic figure championing the empowerment of women through scholarship and learning. She is truly the proud voice of those she has called the “unvoiced.”

(Ambassador Akbar Ahmed is Distinguished Professor of International Relations and holds the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at the American University, School of International Service. He is also a global fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington DC. His academic career included appointments such as Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution; the First Distinguished Chair of Middle East and Islamic Studies at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, MD; the Iqbal Fellow and Fellow of Selwyn College at the University of Cambridge; and teaching positions at Harvard and Princeton universities. Ahmed dedicated more than three decades to the Civil Service of Pakistan, where his posts included Commissioner in Balochistan, Political Agent in the Tribal Areas, and Pakistan High Commissioner to the UK and Ireland)